This morning, thanks to Technology, I was able to remotely attend the funeral mass of Greg Hillis, who passed away from cholangiocarcinoma. It was a bit surreal since I never spent much time with Greg in-person (and since it is always theologically awkward to observe a mass and not actually participate in it; maybe more on that another time)—the vast majority of our interactions were through Twitter. But still, I read much of what he wrote, and so in the least possible “online influencer” sense, there was perhaps a parasocial dynamic at play. It’s not quite like folks around the world watching the funeral of Queen Elizabeth, but it’s not entirely dissimilar: you are peeking into a realm for which you are on the periphery.

At any rate, the homilist mentioned something that caused me to pause a little. But I want to be very clear here: I am not about to dunk on a funeral homily, nor its deliverer. I am merely offering a small amount of reflection based on a shift in emphasis that I find helpful.

He referenced some of what Greg once wrote in his piece on Julian of Norwich, about how we orient our suffering to God’s suffering (and vice-versa). I’m finding that generally, and not just in the context of this particular funeral mass, much of the dialogue around human suffering ends up with the focus on Christ coming alongside us in our suffering. But I don’t find that nearly as comforting as swapping the direction: in this form of suffering, I am able to draw closer to Christ. That seems to me to be the tenor of Scripture (and the first several hundred years of the church). We share in his sufferings (and then share in his glory; Rom. 8:17-18). We participate in his suffering because through that suffering, joy will truly overflow (again, when his glory is revealed; 1 Pet. 4:13). We share in his sufferings and hope for a death like his (Phil. 3:10).

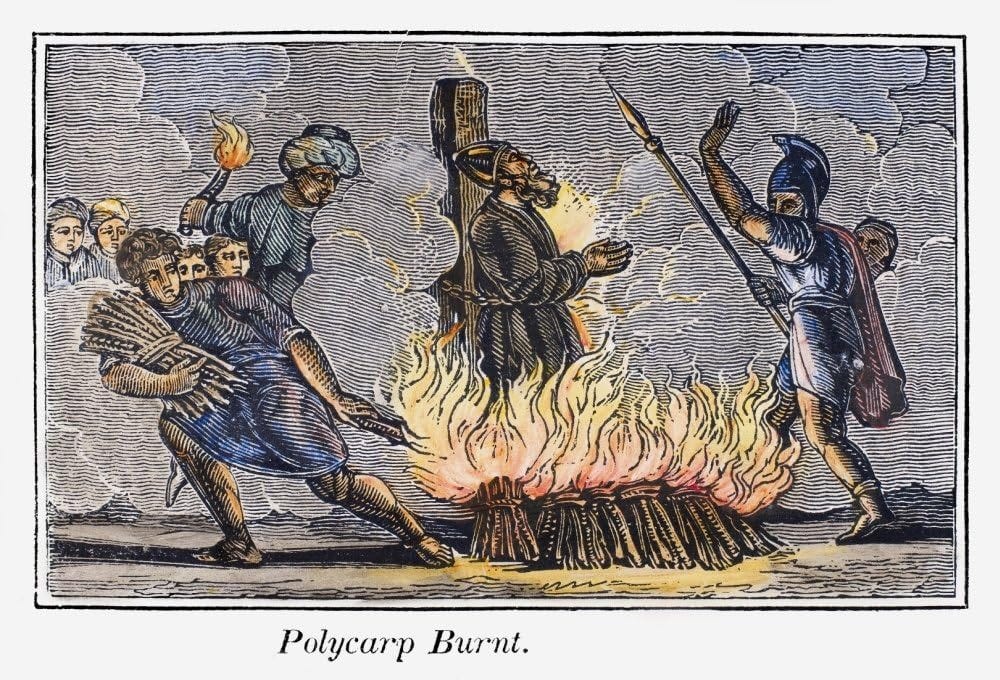

Now, I know: so much of the context of the New Testament, and especially Paul’s letters, involved suffering because of the faith. Not because of some physical impediment. There is a sticky wicket here of particularism vs. universalism. That’s why we had the development of an entire mythology around asceticism and martyrdom. At some point in the popular imagination of early Christians, it was only possible to be close to Christ by denying yourself all that Christ was denied, and though self-crucifixion wasn’t possible, dying a sacrificial death like Christ was.

But what if we temper this impulse? If the point of Christ becoming human was, as so many church fathers pronounce, in order to draw humanity up into him, and if Athanasius or Gregory of Nazianzus or Hilary or Augustine (etc., all following Paul) were right that “what is not assumed by God is not saved”, then what has been assumed by Christ is the entirety of human experience. Which means that we don’t have to be persecuted for our faith, or stabbed in the side, or nailed to a cross and asphyxiated, in order to draw near to Christ. Nor does it mean when he draws near to us that it’s simply like a grief counsellor.

Quick aside: I know Christ’s “power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor. 12:9), but I don’t like how this passage is often applied to human suffering, either. While we really don’t know exactly what Paul meant in talking about a “thorn in the flesh”, I don’t think the weakness being discussed here is some involuntarily received disease. (I also don’t think I’m going to later contradict myself on this point, but I’ll let you be the judge of my hastily applied hermeneutic. 2 Corinthians 12 is…weird.)

I think what Greg said in the closing paragraph of his piece on Julian (and which was read aloud by one of the people sharing remarks at the funeral mass) actually gets the closest to leading where I’m thinking:

Anger with God in the face of suffering makes sense if we think of God as the cause of that suffering or if we perceive God to look upon our suffering with a kindly, but impotent, benevolence. But if we come to understand that God suffers alongside us as one who truly knows what it means to suffer, our anger morphs into love and our suffering mysteriously becomes a means of transformation.

While, yes, God comes alongside us, there ought to be something more. Or rather, there can be more. I don’t think God “caused” my cancer. But I do think I have an opportunity to use this suffering as a path toward God as one able to understand just *infinitesimally minutely more* the suffering experienced by Christ. Having cancer is an opportunity for transformation.

This doesn’t mean I’m happy about it. I’ve suffered a great deal in my life, but I’d take something else if given the choice.

It also doesn’t mean that it’s appropriate to relativize suffering, I think. I am very tired of absolving people from the guilt of telling me their problems—y’know, sharing with me the troubles of their life in a way necessary to the sustenance of friendships—because they pale in comparison to cancer. I’m not singling any one person out here; it’s spectacular how often this happens to me.

I want to say this: It doesn’t matter that I have cancer. You losing your job, or having the flu, or whatever, is still a form of suffering. If Karl Barth is right about human flourishing being about living an integrated life with God, others, and yourself, then these things cause the opposite of flourishing—suffering. So somehow, we’re all in this human-shaped boat of suffering together.

My hope is that by steering the rudder toward Christ, we might learn to suffer better. I don’t exactly know how to do that, but it may mean using the rungs of this cruddy ladder to begin to ascend in a more surefooted way than before.

RIP, Greg.

Epilogue: I think this is why I love participating in the sacrament of the Eucharist—I don’t view it as an opportunity for Christ to get closer to us. He’s already done that by declaring us his body. It is an opportunity for us to join with him; the table is the place where the body gets closest to being in one piece again, before we [socially] fracture ourselves for six days, ironically representing the greater and more ominous fracturing that exists as long as the church is disunited. Again, maybe more on this another day.

Yes. I think our tendency to talk about Christ coming along side of us in our suffering is to make our suffering primary. Our suffering is, of course, primary to us as something that is experienced by us, but it is not primary to God. The point isn't that Jesus suffered so that we have a friend who understands us, but, as you said, so we can become more like him (and I think you are right about the growth of asceticism filling in the gap of external suffering).

Also, you list Gregory twice as the Theologian and Nazianzus. Did you mean Nyssa?

Many good, thought-provoking points here. It does emphasize an important shift in perspective (metanoia), which is much needed. Rather than passively 'waiting' for Christ to draw closer to us (in order to comfort us), we should be actively drawing closer to Him.